I visited the former site of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital ("RVMH"), again last Saturday (3rd December), and this time the tower, Chapel Memorial* and the visitor's centre were all open (if you do plan to visit -esp. the chapel-, do check, these times vary throughout the year, go to: https://www.hants.gov.uk/thingstodo/countryparks/rvcp/visit & https://documents.hants.gov.uk/ccbs/countryside/RVCPMap6.pdf), be advised that you will be charged admittance if you wish to ascend the tower to the top and that the spiral staircase within the tower and climbing it to are most vertigo inducing. I will have to steel myself if I wish to take in the view (I had forgotten my vertigo in this regard but in my defence the effect of the open, red steel, spiral-staircase within the bright white painted brickwork of the tower was Hitchcock-ian -I've been a "flat-lander" too long-).

*Nb. The chapel and tower exhibitions are "memorials" the centre is not a museum.

I have to say that the staff were really, really nice it they are obviously used to the heightened emotional state the place tends to induce in people. If you have a family history you wish to relate they are very happy to hear it and also share their own (it seems that there is, indeed, method to the madness as the people I met all had personal and/or familial reasons for wanting to provide the service they do). One had a relative who served in the artillery in N.Africa and Italy (Monte Cassino), Spike Milligan was in the heavy artillery for both campaigns and my good friend A.Laroche had a great uncle who served in Tobruk was invalided to Malta and then sent off (having been "repaired"), to the hell-on-Earth that was Monte Cassino. According to my friend his uncle was deeply affected by his experience and remained, very obviously, traumatised for the rest of his life. I discussed the grim absurdity of the bombing of the monastery with the member of staff concerned and we agreed that it seems that witnessing the desecration and destruction of such an historic and sacred place (certainly to many of the soldiers on both sides of the conflict), was the straw-that-broke-the-camel's-back for significant numbers of those who witnessed it:

I've always thought that it is a desperate shame that there were no recordings made (or at least there are none that survived -and I don't recall Spike ever mentioning recordings being made in any of his books-), of Spike's trumpet playing during his time at the Battle of Cassino (also known as "The Battle for Rome").

It is a beautiful, autumnal, late-afternoon outside a church hall on the side of a mountain in south-central Italy in 1944. An American colonel and a female adjutant (not his), from staff headquarters arrive in a jeep and they are looking for a British officer. Through the open door the pair can see shadows and movement, they also perceive faint and unusual sounds emanating from within. With the sun gleaming off both his cap and the adjutant the colonel steps into the hallway and begins to make out a group of British Officers and NCOs wobbling, shuffling and occasionally jerking about as if electrocuted by a cattle-prod (or even lightning), and they are making strange sounds something like this; "awwooogleugglllleoggle, iwwwigglyyoggwall, hehehigwooblewoblewooble" and so forth. The Yank Colonel looks on incredulously, finally he manages to catch the eye of one of the British officers, who regards him with scant interest. The American asks; "What are you Limey's doing?!" The officer he has addressed slightly straightens himself, as he would if challenged whilst carefully making his way home from the local public house, on an early New Year's morning, by a young police officer and, seeming to vibrate with only slightly less intensity than before, replies; "Voting for f**king Christmas old-man! What does it look like we're doing?!"

Just another one of those tales dead men don't tell you might say and I was to discover just how apposite the notion is when I began to question the staff concerning sources for information on any of those involved with the hospital whilst it was open. The thing one has to remember is that this was a military hospital so whilst patient confidentiality with regard to medical records was assiduously observed, as it still would be in any civilian hospital, patients at the Royal Victoria were also serving soldiers, as were the staff, and there are strict controls on the keeping of any personal records in the services to this day. Patient or staff; diaries, letters, memoirs and photographs are, I was told, many of them actually considered state secrets. The other problem is that where records do exist they are held not just by the three services (army, navy and air force), but also by the various regiments, ships and squadrons (et.al). The medical staff were also drawn from more than one place, some were from the Royal Army Medical Corps ("RAMC" go to: https://www.army.mod.uk/who-we-are/corps-regiments-and-units/army-medical-services/royal-army-medical-corps/), some were from Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps ("QARANC" go to: https://www.army.mod.uk/who-we-are/corps-regiments-and-units/army-medical-services/queen-alexandras-royal-army-nursing-corps/), and some from the Red Cross (go to: https://www.redcross.org.uk/). Again those in either the RAMC or QARANC would be court-martial-ed if they were to divulge any information with regard to their service. This makes researching the experiences of those involved with the RVMH extremely challenging.

An author who has, at least, made the attempt would appear to be Philip Hoare, quote: "Spike Island* (the name its inhabitants gave the area centuries before), is as singular as Hoare's previous work: simply, his chosen subject is so interesting it is astonishing to consider that no one has written of it before. However, few could combine such rigorous scholarly accuracy with Hoare's narrative flair. His literary tones - ghostly, haunting, reminiscent of du Maurier - find their echo in Netley's grim history.

This history is even greater, more labyrinthine, than the hospital itself, with stories spawning still more stories, each as fascinating as the one before. Victims of the Boer War and both world wars found themselves here; Wilfred Owen was a patient. An 'eerie, depressing place', doctors would experiment on themselves in the laboratories and, it was rumoured, use German PoWs as human guinea pigs. In the psychiatric wing, shell-shock victims were treated as harshly as the decades dictated and Hoare's descriptions of these psychological casualties are deeply affecting": https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/apr/22/historybooks.features In an article in the Guardian in the August of 2014 Hoare writes, quote; "The Royal Victoria Military Hospital at Netley was not only England's biggest building, but also its "largest palace of pain", according to a 1900 report. Set on the shores of Southampton Water in Hampshire, it was created in response to the Crimean war, and designed to serve an empire. It would end up ministering to apocalypse. During the first world war, this sprawling brick behemoth – a quarter of a mile long – became a microcosm of what was happening across the English Channel.

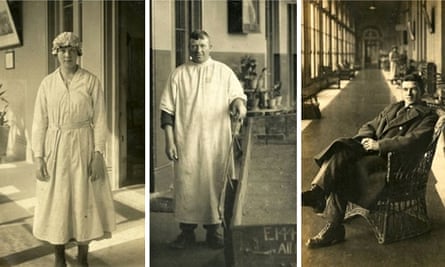

Now, a century later, a remarkable album of photographs has come to light to document the men and women who worked at Netley, who were healed there, or who died there. Published here for the first time, these poignant and oddly immediate images reveal the extent of this global conflict, and the way it involved civilians as well as serving men and women. Their faces tell untold stories. They were far from the action, but they were the ordinary people who serviced and fed the insensate and insatiable monster that was the war.

When I began to write my book Spike Island: The Memory of a Military Hospital, I was amazed at how few records remained to document Netley's story. The hospital stood, from its foundation in 1856 to its demolition in 1966, for more than a century. Yet almost nothing remained in the public archive to commemorate it. What emerged instead were family memories of 1914-18, years that saw Netley's resources at peak demand.

Thousands of men and women lived and died in this place, remembered in sepia-scored letters and postcards, and pictures taken by local photographers. Only a precious few, such as this album, survive to reclaim a site that was once world-famous. When Conan Doyle published his first Sherlock Holmes mystery, A Study in Scarlet, he told his readers that Dr Watson trained as an army doctor at Netley – its name was so well known that the author did not need to explain any further**": https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/21/royal-victoria-hospital-netley-ww1-first-world-war-photographs-documentary-philip-hoare

*As the day is long I did not know this until I discovered the Guardian article whilst composing this post (and after I had referenced Milligan -"was that 50milligans doctor?"-). Their part in my downfall hey? #Gruaniad

**Italics mine. Yet the hospital has faded from public consciousness along with its story for as Britain continues to posture (although "mutton-dressed-as-lamb"), on the world's stage the true cost of imperial Britannia, needs-must, remains hidden.

Hoare is clearly well aware that there is precious little with which to tell either the hospital's story or, by extension, the wider story of the cost of empire.

This puts any film-maker in an invidious position for no-one (esp. when tackling such a delicate subject), wants to leave themselves open to the accusation of having put their own words into their character's mouths. So how does one characterise the dramatis personae? There is one well known patient, Wilfred Owen, quote; "One wet night during this time he was blown into the air while he slept. For the next several days he hid in a hole too small for his body, with the body of a friend, now dead, huddled in a similar hole opposite him, and less than six feet away. In these letters to his mother he directed his bitterness not at the enemy but at the people back in England “who might relieve us and will not.”

Having endured such experiences in January, March, and April, Owen was sent to a series of hospitals between May 1 and June 26, 1917 because of severe headaches. He thought them related to his brain concussion, but they were eventually diagnosed as symptoms of shell shock, and he was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh to become a patient of Dr. A. Brock, the associate of Dr. W.H.R. Rivers, the noted neurologist and psychologist to whom Siegfried Sassoon was assigned when he arrived six weeks later."..."When Sassoon arrived, it took Owen two weeks to get the courage to knock on his door and identify himself as a poet. At that time Owen, like many others in the hospital, was speaking with a stammer. By autumn he was not only articulate with his new friends and lecturing in the community but was able to use his terrifying experiences in France, and his conflicts about returning, as the subject of poems expressing his own deepest feelings.": https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/wilfred-owen

.JPG) |

| Iron Lung used for Poison Gas Victims |

Dulce et Decorum Est

I'll let my photographs speak for themselves for a while:

There is one very interesting exhibit with regard to D-block (which is where Wilfred Owen was treated), concerning the film "War Neurosis":

All five parts are viewable here: https://www.google.com/search?q=War+Neurosis+film+&sxsrf=ALiCzsb_T6BLRWWGfXvNxG0-57vIyYtFow%3A1670251823408&source=hp&ei=LwWOY6KQFpG2a93KvJAB&iflsig=AJiK0e8AAAAAY44TP6MmOcBtoridRxl8MbuuEzQ6RR4I&ved=0ahUKEwji4_f03OL7AhUR2xoKHV0lDxIQ4dUDCAk&uact=5&oq=War+Neurosis+film+&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAMyBQgAEIAEMgUIABCABDIFCAAQgAQyBQgAEIAEMgYIABAWEB4yBggAEBYQHjIGCAAQFhAeMggIABAWEB4QCjIGCAAQFhAeMgYIABAWEB5QAFiGF2C5GWgAcAB4AYAB-gSIAewKkgELMC4xLjEuMS4wLjGYAQCgAQE&sclient=gws-wiz#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:55bc1cb1,vid:AL5noVCpVKw,st:59 and they are detailed here: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/p5993re4

The exhibit concerns the manufactured and fraudulent presentation of the facts by "War Neurosis"..

It must be remembered that the film was made whilst WW1 was still going on, rather obviously the British state wanted to give the impression that whilst the weapons being employed for causing mass slaughter were innovative and modern so was the standard of treatment of the casualties they caused (as if all could be "cured" -incl. the enemies of empire-).

The Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery (Netley)

"Where did you get that hat?"

.JPG) |

| A priest of the hospital (God alone knows what he went through) |

A soldier of the Hampshire Regiment, quote: "The 2nd Hampshire was originally based in Aldershot, but were mobilised when war was declared. They left for France as part of the 1st Division which formed a major part of the British Expeditionary Force."..."Disorder surrounded the withdrawal to Dunkirk, but the Battalion withdrew in good order. They arrived in Proven at 4pm on 29th May, having travelled over 45 miles in 2 days, under very difficult conditions. At Hondschoote they were ordered to destroy all vehicles and move to Uxem. On 30th May, Uxem was shelled heavily, but the Battalion held the position, and on 1st June was ordered to withdraw to Dunkirk at 5pm that day. It was a race against time; the enemy worked incessantly to cut off the Allies last chance of escape. However, the 2nd Hampshire reached the beach and took their place in the long, orderly queues, getting home via ships of every kind and arriving at different ports all along the coast. Nevertheless, the Hampshires arrived home complete with all their arms and equipment, and had suffered very few casualties.*": https://www.royalhampshireregiment.org/about-the-museum/timeline/dunkirk-1939-1940/

*Italics mine. Few perhaps but not none, Private R.T.Wallis died in the July aged 25, presumably of wounds sustained in France. well at least he came home (just didn't stay very long). I picked his grave to photograph because of the Hampshire insignia, it was not until I reviewed my photos today that I realised that the man buried was in the same battle during which my great uncle William was killed.

Wobblin' Tommies?

Whilst imagining the cast for Wobblin' Tommies one character, a "shot-away" artillery corporal (played by Daniel Radcliffe), came to mind and, as I have begun to research more seriously, a scene with a senior medical officer (the character played by Benedict Cumberbatch), began to develop, it goes something like this (it's a closing scene too so should be full of pathos); Corp; "Do you know what you are sending those guys back to?" Officer does not reply looks at NCO. Corp; "You don't have a clue do you? Not a f**king clue!" (NCO not caring that he was swearing at an officer) "You're not going to be there are you?" Officer gathers himself and says; "You're not going to be there either." Pause; "Yes I am!" Officer; "What?" Corp; "I'm going back (looks at officer out of the top of his eyes)!" Officer; "What?" Corp; "I can't let them go alone....back to that" Officer, nearly speaks, corp interrupts; "You don't understand do you? I can't let them go alone...I'll tell you something though, we'll be waiting, we'll be waiting for you to join us..you won't be alone either!" That's the scene, the plot device would be that someone pulled some strings for the corp. (he could be an infantry soldier..have to see), that..yeah..maybe he was in love with a nurse from a different class and that didn't work out (she was transferred etc.), he had been shell-shocked and developed a great affection for many of the other patients (a group from his own regiment perhaps), ..

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment